JS TDD Ohm

Welcome to part 4 of this ongoing series on test-driven development (TDD) in JavaScript. So far we've covered:

- Part 1 - the basic principles of test-driven development, showing unit testing using Jest;

- Part 2 - expanding to higher level testing, using Cypress for E2E and Jest for integration (and unit) testing of a simple React app with Testing Library; and

- Part 3 - introducing some more ideas about isolating your code for testing using test doubles.

If you haven't already been through those I'd suggest revisiting at least the first one, as it introduces some terminology and ideas I'll use here.

This time we're going to dive into test-driving HTTP APIs and talk a bit more about how we can use testing to support us in designing the code we're working on.

Requirements

The prerequisites here are the same as the previous articles:

- *nix command line: already provided on macOS and Linux; if you're using Windows try WSL or Git BASH;

- Node (16+ recommended, Jest 29 is only compatible with recent LTS versions; run

node -vto check) and NPM; and - Familiarity with ES6 JavaScript syntax.

In addition, given the domain for this post, you'll need:

- Familiarity with HTTP requests and responses; and

- Familiarity with Express.

Again please carefully read everything, and for newer developers I'd recommend typing the code rather than copy-pasting.

Setting the scene [1/9]

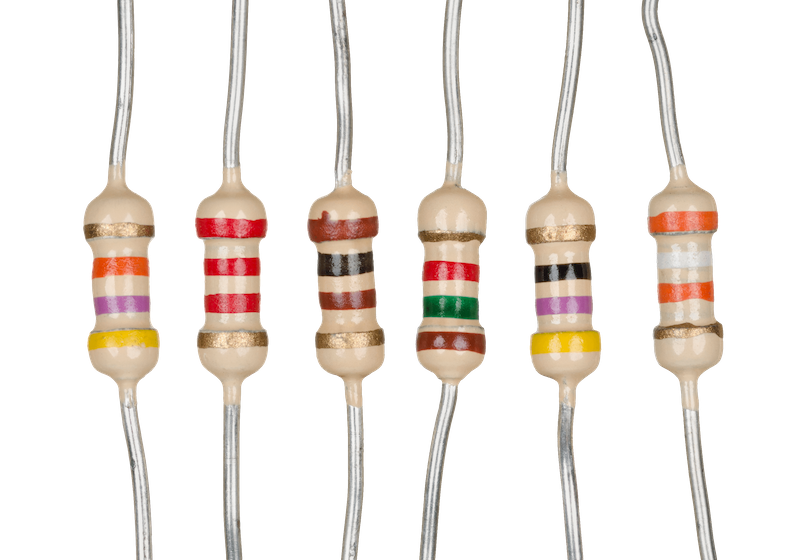

We're going to be tackling a more realistic case than rock, paper, scissors this time. Our customer, JonFX, sells guitar pedal kits that you construct yourself at home. These kits contain set of instructions and a bunch of electrical components, including resistors:

There are three representations of resistance (measured in Ohms, Ω) in use within this ecosystem. For example, given a 22,000Ω resistor, it can be represented as:

- A number,

22_000; - A shorthand string,

"22K"; or - A set of bands on the physical component, e.g. red, red, orange .

Our customer has noted that people sometimes have difficulty converting between these representations, and asked us to build something to help solve the problem.

How do we prioritise which representations we should focus on to start with? We want to deliver the most valuable thing first, so let's do some analysis. There are three personas who work with these representations:

- Debbie the designer: Debbie designs the circuits, and generally works with the number representation. Once a design is complete the values are recorded in a manifest using the shorthand notation;

- Colin the customer: Colin wants to buy and build one of the kits, which will include the manifest and the components with their bands; and

- Parul the packer: When Colin orders a kit, Parul is responsible for selecting the components based on the manifest, boxing them up and shipping them out.

Parul and Debbie both work with resistors and other electrical components on a very regular basis, so they probably don't need reminding what the bands mean, and if not there are various non-software interventions we could use to make their lives easier (for example, the boxes Parul is selecting components from could have a picture of the relevant bands and the shorthand printed in large letters to aid selection and refilling). But it might be a while since Colin built his last kit (or he may even be a first-time customer), so that's the persona most likely to need help and therefore the highest value software would focus on the conversion between bands and shorthand, especially when you consider that the company will have far more Colins (thousands) than Paruls (ten) or Debbies (one).

Let's capture that as a user story that we can refer back to if we need reminding what we're working towards:

As a customer

I want to convert a set of bands to a shorthand string

So that I can match a given resistor to the diagram

For this exercise, we're going to be building the backend for a web UI; an acceptance criterion based on the above examples might be:

Given an input of the bands red, red, orange

When the client makes a request

Then the response contains the shorthand

"22K"

Note: for the sake of simplicity we will be working on an implementation that can convert values from 10Ω (or 100Ω for three value bands) up to but not including 1,000,000,000Ω.

Welcome to the resistance [2/9]

As shown above, physical resistors have coloured bands which indicate their resistance. The "rules of resistors" that we'll be following are:

- A resistor must have two or three value bands, unless it's a 0Ω resistor (which must have only a single black value band);

- The first value band must not be black, unless it's a 0Ω resistor; and

- A resistor must have a single multiplier band.

The band colours indicate numbers via the following mapping:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| black | brown | red | orange | yellow | green | blue | violet | grey | white |

The numerical resistance is determined by taking the two or three value bands as the first two or three digits, then adding the number of zeros specified by the multiplier band to the end, e.g.:

- Value: blue - 6

- Value: grey - 8

- Multiplier: green - 5

becomes 6,800,000Ω (6 then 8 then 5 zeros). You could also calculate this as ((6 * 10) + 8) * (10 ** 5).

The shorthand form is created by replacing the left-most comma with M (for "mega", meaning a factor of one million) and dropping all trailing zeros; in this case "6M8". For values between 1,000Ω and 999,999Ω the comma is replaced with K (for "kilo", meaning a factor of one thousand) instead, hence the 22,000Ω above becomes "22K". For values less than 1,000Ω the decimal point is replaced with R, so e.g. 150Ω (bands brown, green, brown) would be represented as "150R".

Here are a few more examples, or for more details you can read about this electronic colour code on Wikipedia:

| Numeric (Ω) | Shorthand | Bands |

|---|---|---|

| 22 | "22R" |

red, red, black |

| 12,700 | "12K7" |

brown, red, violet, red |

| 330,000 | "330K" |

orange , orange , black, orange |

| 8,200,000 | "8M2" |

grey, red, green |

How can we represent this at the API level? There are a few options, but for the purposes of working through this exercise let's say:

- The request method will be

GET; - The request path will be

/resistance; - The bands will be provided as a query parameter named

bands; - The response status code on success will be

200("OK"); and - The response body on success will be the shorthand representation as plain text.

Using cURL, this might look like (assuming an environment variable URL has been set pointing to our API server):

$ curl "$URL/resistance?bands=brown&bands=red&bands=violet&bands=red"

12K7

None more black [3/9]

Let's get started by creating a new NPM package to hold our API:

$ mkdir resistance

$ cd $_

$ git init

Reinitialized existing Git repository in path/to/resistance/.git/

$ git commit --allow-empty --message 'Initial commit'

[main (root-commit) 7c30cd9] Initial commit

$ npm init --yes

Wrote to path/to/resistance/package.json:

{

"name": "resistance",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"keywords": []

}

$ git add .

$ git commit --message 'Create NPM package'

[main 6c30da5] Create NPM package

1 file changed, 12 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 package.json

We'll use Jest again for testing, and add Supertest as an adapter between the test runner and the API, to make it easier to make requests and assert on the responses (I've explained why I think this is better than just using e.g. Axios to make the requests here):

$ npm install --save-dev jest supertest

added 305 packages, and audited 306 packages in 7s

38 packages are looking for funding

run `npm fund` for details

found 0 vulnerabilities

$ echo node_modules/ > .gitignore

$ git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: package.json

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.gitignore

package-lock.json

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

$ git add .

$ git commit --message 'Install test dependencies'

[main 56d2180] Install test dependencies

3 files changed, 6553 insertions(+), 1 deletion(-)

create mode 100644 .gitignore

create mode 100644 package-lock.json

Create app.test.js and write a test. Let's start with the simplest possible case; the 0Ω resistor, a single black band:

const request = require("supertest");

describe("resistance API", () => {

it("returns 0R for a single black band", () => {

return request(app)

.get("/resistance")

.query({ bands: ["black"] })

.expect(200, "0R");

});

});

Here you can see how Supertest's API lets us specify the request to make (method, path and query parameters) and assert on the response (status code and body). Set up Jest as the test runner using NPM's pkg command:

$ npm pkg set scripts.test=jest

What will happen when you run the test? Call the shot, then use npm test to run it.

$ npm test

> [email protected] test

> jest

FAIL ./app.test.js

resistance API

✕ returns 0R for a single black band (1 ms)

● resistance API › returns 0R for a single black band

ReferenceError: app is not defined

3 | describe("resistance API", () => {

4 | it("returns 0R for a single black band", () => {

> 5 | return request(app)

| ^

6 | .get("/resistance")

7 | .query({ bands: ["black"] })

8 | .expect(200, "0R");

at Object.app (app.test.js:5:20)

Test Suites: 1 failed, 1 total

Tests: 1 failed, 1 total

Snapshots: 0 total

Time: 0.224 s, estimated 1 s

Ran all test suites.

Hopefully you predicted that: app wasn't defined, the test crashed before even getting the chance to fail. So let's give it an app to test! Start by installing Express:

$ npm install express

added 53 packages, and audited 359 packages in 880ms

40 packages are looking for funding

run `npm fund` for details

found 0 vulnerabilities

Create a new file app.js, and set up a basic Express application:

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

module.exports = app;

then add the import into app.test.js:

const request = require("supertest");

+

+ const app = require("./app");

describe("resistance API", () => {

What will happen when we re-run the test now? Call the shot, then run it again.

$ npm test

> [email protected] test

> jest

FAIL ./app.test.js

resistance API

✕ returns 0R for a single black band (18 ms)

● resistance API › returns 0R for a single black band

expected 200 "OK", got 404 "Not Found"

8 | .get("/resistance")

9 | .query({ bands: ["black"] })

> 10 | .expect(200, "0R");

| ^

11 | });

12 | });

13 |

at Object.expect (app.test.js:10:8)

----

at Test._assertStatus (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:252:14)

at node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:308:13

at Test._assertFunction (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:285:13)

at Test.assert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:164:23)

at Server.localAssert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:120:14)

Test Suites: 1 failed, 1 total

Tests: 1 failed, 1 total

Snapshots: 0 total

Time: 0.232 s

Ran all test suites.

That's a bit more like it, the test is now failing (rather than crashing) and we're getting feedback at the HTTP API level (404 Not Found status code instead of the expected 200 OK). Let's handle that endpoint and move the failure a bit further along; add the code to app.js to handle the GET request and immediately return 200 OK:

app.get("/resistance", (req, res) => {

res.sendStatus(200);

});

Now we should see a failure for the body of the response, rather than the status code:

● resistance API › returns 0R for a single black band

expected '0R' response body, got 'OK'

8 | .get("/resistance")

9 | .query({ bands: ["black"] })

> 10 | .expect(200, "0R");

| ^

11 | });

12 | });

13 |

at Object.expect (app.test.js:10:8)

If not, you may be handling the wrong path or method; double-check that the code in app.js matches up with the request defined in app.test.js.

Finish up the first step by updating the handler so that the test passes, then make a commit:

$ git add .

$ git commit --message 'Implement 0 Ohm resistor'

[main 51abbe9] Implement 0 Ohm resistor

4 files changed, 964 insertions(+), 31 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 app.js

create mode 100644 app.test.js

Note: test-driving the development has already influenced one part of our system's design - wanting to access the application directly means we've exported it rather than immediately calling app.listen to start it up. If you'd like to try out the server locally (e.g. using cURL or Postman) while you're working on it, create the following server.js:

const app = require("./app.js");

const PORT = parseInt(process.env.PORT || "3000", 10);

app.listen(PORT, () => console.log(`listening on ${PORT}`));

then npm install --save-dev nodemon and update the scripts in package.json with the following:

"scripts": {

+ "dev": "nodemon ./server.js",

"test": "jest"

}

Now npm run dev will start the app, and restart whenever you save changes. But you might find that you don't need to try out the server manually, because all the tests mean you're already confident that it works, and that's worth reflecting on!

Unhappy path to design [4/9]

At this point you might be tempted to jump straight to an example like the 22kΩ resistor in the introduction, writing something like:

it("returns 22K for red, red, orange", () => {

return request(app)

.get("/resistance")

.query({ bands: ["red", "red", "orange"] })

.expect(200, "22K");

});

But bear in mind that this is an HTTP API. Anyone can make a request to it, and they might not send one that's well-formed. In my case, where it's expecting a request like /resistance?bands=black, what if there isn't a query parameter? I've found this status code flowchart really useful for figuring out a semantically appropriate response; working through that I get down to 400 Bad Request. So let's write that test:

it("returns 400 if query missing", () => {

return request(app)

.get("/resistance")

.expect(400, "Bad Request");

});

Follow the TDD process:

- Call the shot;

- Run the test;

- Ensure it fails usefully (edit the test and repeat steps 1 and 2 as needed);

- Get it passing; and

- Make a commit.

Remember: never rely on your clients to make valid requests. Even if you only intend for the API to be consumed by e.g. a React app you're maintaining, always check that input validation and authentication is applied correctly; it's trivial to make a request without using the UI.

Next, what if there is a bands query parameter but its value isn't black? That's a structurally valid request, it has the query parameter, but e.g. /resistance?bands=blue is semantically invalid; there's no real resistor with a single blue band. From the above flowchart, I get to 422 Unprocessable Entity. So let's write a second test for that.

it("returns 422 for a single non-black band", () => {

return request(app)

.get("/resistance")

.query({ bands: ["blue"] })

.expect(422, "Unprocessable Entity");

});

The temptation here might be to do something like this:

app.get("/resistance", (req, res) => {

const { bands } = req.query;

if (!bands) {

return res.sendStatus(400);

} else if (bands.length !== 1 || bands[0] !== "black") {

return res.sendStatus(422);

}

res.send("0R");

});

However, this is mixing up two very important concepts. We have two domains here, transport (HTTP requests and responses, things like paths, query parameters and status codes) and business (resistors and their resistance values). Splitting this out into those two domains might look like:

| Request | Transport | Business |

|---|---|---|

GET /resistance |

"A request with no bands query parameter is bad." -> 400 |

N/A |

GET /resistance?bands=blue |

"An invalid resistor isn't processable." -> 422 |

"A resistor with a single blue band isn't valid." |

Here you can see the split described above - the left-hand side is about HTTP APIs, the right-hand side is about resistors. While handling a structurally invalid request can be done entirely at the transport level, handling a semantically invalid request is a business level question.

So let's take this opportunity to split out a service in service.js to handle the business domain:

module.exports.resistance = (bands) => "0R";

and use that in the app:

const { resistance } = require("./service");

// ...

app.get("/resistance", (req, res) => {

const { bands } = req.query;

if (!bands) {

return res.sendStatus(400);

}

res.send(resistance(bands));

});

This is a simple refactor, the 200 and 400 tests should still pass, and the 422 test should still fail (you can comment it out or skip it to double-check). It also gives us a new boundary to test at, we can exercise the service code directly in service.test.js:

const { resistance } = require("./service");

describe("resistance", () => {

it("returns 0R for a single black band", () => {

expect(resistance(["black"])).toBe("0R");

});

});

You can run these low-level tests on their own by passing the file name as an argument to Jest, npm test -- service. So how should we handle an invalid band? Again this gives us a chance to do some design, think through how the function should behave by writing the test before the implementation. For example:

- We could return

nullfor cases where the bands aren't valid,expect(resistance(["red"]).toBeNull(), but if all we get back from the function in the failing case isnullthat doesn't tell us much about what the problem was; - We could return a string describing the problem, but that would make it very difficult for the controller to distinguish between valid and invalid cases to send the appropriate responses;

- We could return an object,

expect(resistance(["red"]).toEqual({ error: "..." }), but that doesn't exactly scream "your input made no sense".

I would say the right thing to do here is to throw an error, which can have a message explaining what the problem was. Remember that you have to pass a function when you expect an error to be thrown, to defer the execution of the thing you're testing, otherwise (with e.g. expect(resistance["blue"])).toThrow(...)) the error is thrown before expect gets called:

it("throws an error for a single non-black band", () => {

expect(() => resistance(["blue"])).toThrow("Invalid bands: blue");

});

Note: it seems to be a popular pattern to write an exception with a status code for this kind of thing, e.g.:

// custom error:

class CustomError extends Error {

constructor(status, message) {

super(message);

this.status = status;

}

}

// in the service:

throw new CustomError(422, "...");

// in the controller/middleware:

if (err instanceof CustomError) {

res.status(err.status).send(err.message);

}

I think that this is bad design - the whole point of extracting the service was to isolate our business logic from details of the transport layer. Imagine we reused the core service with a different transport layer, e.g. a CLI wrapper to allow usage on the command line:

$ ./resistance.js yellow violet black

4K7

Now what does the status on the error mean, what is 422 in the context of a CLI? We've re-coupled our core domain/business logic back to the transport layer, we might as well have written everything in the controller!

Call the shot, run the test, check the diagnostics:

● resistance › throws an error for a single non-black band

expect(received).toThrow(expected)

Expected substring: "Invalid bands: blue"

Received function did not throw

7 |

8 | it("throws an error for a single non-black band", () => {

> 9 | expect(() => resistance(["blue"])).toThrow("Invalid bands: blue");

| ^

10 | });

11 | });

12 |

at Object.toThrow (service.test.js:9:40)

Get that test passing at the service level, then run all of the tests to bring the integration tests back in (remember to call the shot):

$ npm test

> [email protected] test

> jest

FAIL ./app.test.js

● resistance › returns 0R for a single black band

expected 200 "OK", got 500 "Internal Server Error"

14 | .get("/resistance")

15 | .query({ bands: ["black"] })

> 16 | .expect(200, "0R");

| ^

17 | });

18 |

19 | it("returns 422 for a single non-black band", () => {

at Object.expect (app.test.js:16:8)

----

at Test._assertStatus (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:252:14)

at node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:308:13

at Test._assertFunction (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:285:13)

at Test.assert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:164:23)

at Server.localAssert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:120:14)

● resistance › returns 422 for a single non-black band

expected 422 "Unprocessable Entity", got 500 "Internal Server Error"

21 | .get("/resistance")

22 | .query({ bands: ["blue"] })

> 23 | .expect(422, "Unprocessable Entity");

| ^

24 | });

25 | });

26 |

at Object.expect (app.test.js:23:8)

----

at Test._assertStatus (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:252:14)

at node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:308:13

at Test._assertFunction (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:285:13)

at Test.assert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:164:23)

at Server.localAssert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:120:14)

PASS ./service.test.js

Test Suites: 1 failed, 1 passed, 2 total

Tests: 2 failed, 3 passed, 5 total

Snapshots: 0 total

Time: 0.26 s, estimated 1 s

Ran all test suites.

That's unfortunate; two of the tests are failing. I was expecting only one failure, we still handle the single black band case correctly. And even worse we don't see very much information about why.

Note: this is a good motivation for running the code in a known-failing state, as TDD encourages - you get a preview of what errors in production would look like, and it this case it's told us we need better observability ("o11y")!

To help with debugging, add the following Express middleware to the end of app.js to ensure we see any unhandled errors in the server logs:

app.use((err, req, res, next) => {

if (!req.headersSent) {

console.error(err);

res.sendStatus(500);

}

next(err);

});

and re-run the tests (I've trimmed any error tracebacks to exclude external code - they're very long otherwise):

$ npm t

> [email protected] test

> jest

FAIL ./app.test.js

● Console

console.error

Error: Invalid bands: black

at Object.<anonymous>.module.exports.resistance (path/to/resistance/service.js:5:9)

at resistance (path/to/resistance/app.js:12:12)

...

15 | app.use((err, req, res, next) => {

16 | if (!res.headersSent) {

> 17 | console.error(err);

| ^

18 | res.sendStatus(500);

19 | }

20 | next(err);

at error (app.js:17:13)

...

console.error

Error: Invalid bands: blue

at Object.<anonymous>.module.exports.resistance (path/to/resistance/service.js:5:9)

at resistance (path/to/resistance/app.js:12:12)

...

15 | app.use((err, req, res, next) => {

16 | if (!res.headersSent) {

> 17 | console.error(err);

| ^

18 | res.sendStatus(500);

19 | }

20 | next(err);

at error (app.js:17:13)

...

● resistance API › returns 0R for a single black band

expected 200 "OK", got 500 "Internal Server Error"

8 | .get("/resistance")

9 | .query({ bands: ["black"] })

> 10 | .expect(200, "0R");

| ^

11 | });

12 |

13 | it("returns 400 if query missing", () => {

at Object.expect (app.test.js:10:8)

----

at Test._assertStatus (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:252:14)

at node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:308:13

at Test._assertFunction (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:285:13)

at Test.assert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:164:23)

at Server.localAssert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:120:14)

● resistance API › returns 422 for a single non-black band

expected 422 "Unprocessable Entity", got 500 "Internal Server Error"

21 | .get("/resistance")

22 | .query({ bands: ["blue"] })

> 23 | .expect(422, "Unprocessable Entity");

| ^

24 | });

25 | });

26 |

at Object.expect (app.test.js:23:8)

----

at Test._assertStatus (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:252:14)

at node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:308:13

at Test._assertFunction (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:285:13)

at Test.assert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:164:23)

at Server.localAssert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:120:14)

PASS ./service.test.js

Test Suites: 1 failed, 1 passed, 2 total

Tests: 2 failed, 3 passed, 5 total

Snapshots: 0 total

Time: 0.384 s, estimated 1 s

Ran all test suites.

I was expecting Invalid bands: blue, but Invalid bands: black? That's the one case we thought we'd handled! Try debugging to find out what's going on; put a breakpoint on the first line of the controller and then run the tests with a debugger attached (e.g. in Visual Studio Code run npm test in the JavaScript Debug Terminal, in WebStorm debug the test from the editor).

Note: another good motivation for writing tests, it gives you a really easy entrypoint for debugging small sections of your program.

When you do so you should find out that req.query is { bands: "black" } - bands is not an array. This happens because of the way Express deserialises query parameters, ?foo=bar becomes { foo: "bar" } whereas ?foo=bar&foo=baz gives { foo: ["bar", "baz"] }.

So where do we fix it? From a design perspective I would say that the interface to our service that our unit tests describe is correct - if we were calling that function from anywhere else (e.g. imagine we also had a CLI tool or a desktop app) we'd be passing in an array of strings. So this is something that the transport layer for our API should be handing:

}

- res.send(resistance(bands));

+ res.send(resistance(Array.isArray(bands) ? bands : [bands]));

});

This keeps a very neat split - the transport layer is all about converting between HTTP and our service representation, an array of strings, then the service is purely about resistors and their bands. Call the shot and run the tests again:

$ npm test

> [email protected] test

> jest

FAIL ./app.test.js

● Console

console.error

Error: Invalid bands: blue

at Object.<anonymous>.module.exports.resistance (path/to/resistance/service.js:3:11)

at resistance (path/to/resistance/app.js:15:12)

...

18 | app.use((err, req, res, next) => {

19 | if (!req.headersSent) {

> 20 | console.error(err);

| ^

21 | res.sendStatus(500);

22 | }

23 | next(err);

at error (app.js:20:13)

...

● resistance API › returns 422 for a single non-black band

expected 422 "Unprocessable Entity", got 500 "Internal Server Error"

21 | .get("/resistance")

22 | .query({ bands: ["blue"] })

> 23 | .expect(422, "Unprocessable Entity");

| ^

24 | });

25 | });

26 |

at Object.expect (app.test.js:23:8)

----

at Test._assertStatus (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:252:14)

at node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:308:13

at Test._assertFunction (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:285:13)

at Test.assert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:164:23)

at Server.localAssert (node_modules/supertest/lib/test.js:120:14)

PASS ./service.test.js

Test Suites: 1 failed, 1 passed, 2 total

Tests: 1 failed, 4 passed, 5 total

Snapshots: 0 total

Time: 0.342 s, estimated 1 s

Ran all test suites.

That's much better, we only have one failing test and can see the error at the business level, so we just need to catch it in app.js and respond appropriately to the request to get the tests passing:

$ npm test

> [email protected] test

> jest

PASS ./app.test.js

PASS ./service.test.js

Test Suites: 2 passed, 2 total

Tests: 5 passed, 5 total

Snapshots: 0 total

Time: 0.353 s, estimated 1 s

Ran all test suites.

Once you're there, make a commit:

$ git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: app.js

modified: app.test.js

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

service.js

service.test.js

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

$ git add .

$ git commit --message 'Handle error cases'

[main 0e5b121] Handle error cases

4 files changed, 49 insertions(+), 1 deletion(-)

create mode 100644 service.js

create mode 100644 service.test.js

Double trouble [5/9]

An obvious next step at this point is to test what happens with two bands, which is also invalid according to our rules. Let's add a bit more structure to the low-level test cases and add one for two bands:

const { resistance } = require("./service");

describe("resistance", () => {

describe("one band", () => {

it("returns 0R for a single black band", () => {

expect(resistance(["black"])).toBe("0R");

});

it("throws an error for a single non-black band", () => {

expect(() => resistance(["blue"])).toThrow("Invalid bands: blue");

});

});

describe("two bands", () => {

it("throws an error", () => {

expect(() => resistance(["black", "blue"])).toThrow("Invalid bands: black,blue");

});

})

});

It's worth noting that I've chosen to have "black" as the first of two bands specifically; this was a valid first band for a 0Ω resistor, but isn't otherwise. Any two-band "resistor" is invalid, but using this test case rules out the possibility that we only check whether the first band is black (and not e.g. how many there are).

Call the shot, run the test. If it fails (it may not, depending on how you've implemented the service so far!) then get it passing. We already know that the API will respond 422 if the service throws an error, so we're done; make a commit:

$ git commit --message 'Error for two bands'

[main 48863a8] Error for two bands

1 file changed, 13 insertions(+), 5 deletions(-)

Plotting a course [6/9]

Now we're in a nice position - we've designed and implemented an API, factored our app into transport and business domains, and are testing the integration across three cases:

- No bands - structurally invalid, service doesn't get called, 400 response;

- One black band - service gets called, 200 response with its return value; and

- One non-black band or two bands - semantically invalid, service gets called, 422 response on error.

Sure, we're only dealing with a single, trivial valid case: a 0Ω resistor, with a single black band (which is basically just a wire in the packaging of a resistor!) Our code isn't going to help our end users much at this stage, but we've set the foundations to be able to confidently and rapidly iterate on the core functionality. And if the user does have a resistor with a single black band it gives them the correct answer!

Now, how to approach the more useful cases and actually return some non-zero answers?

In general, when I'm trying to work my way through a problem like this, I try to think about what the next simplest step is - not just in the implementation to get the test passing, but in the logic to write a failing test.

Let's keep using the 22,000Ω/"22K" case we started with. Thinking about the three bands we are using, I'd propose that:

- The second band is the simplest to deal with, as it can represent any value 0-9 (

"20K","21K", ...); then - The first band is the next simplest, as it can represent 1-9 (

"12K","22K", ...) but not 0 (throws an error leading to 422 response status); and finally - The third is the most complex, as both the character and its position can change (

"22R","220R", ...).

To keep us on track as we work towards the result, start with an integration-level test for a different example, one we're not actually going to reach until all three bands are handled. E.g. if the unit-level cases are based around the 22,000Ω example, use the 6,800,000Ω example for the integration-level case. That stops us getting overexcited and shipping once we've handled both value bands but not yet the multiplier. The alternative would be to ensure that cases that aren't yet supported explicitly throw an error, returning a 422 status, which means adding extra tests early on then deleting them as they become irrelevant (this is also an acceptable part of TDD).

So work through the cases in that order, writing parameterised tests for each group. By the time you're finished the suite at the service level should look something like this:

describe("resistance", () => {

describe("one band", () => {

// ...

});

describe("two bands", () => {

// ...

});

describe("three bands", () => {

[/* ... */].forEach(() => {

// second band cases

});

it("throws an error for a leading black band", () => {

expect(() => resistance(["black", "red", "orange"]))

.toThrow("Invalid bands: black,red,orange");

});

[/* ... */].forEach(() => {

// other first band cases

});

[/* ... */].forEach(() => {

// third band cases

});

});

});

Giving test outputs like:

$ npm test -- --verbose

> [email protected] test

> jest --verbose

PASS ./app.test.js

resistance API

✓ returns 0R for a single black band (17 ms)

✓ returns 400 if query missing (6 ms)

✓ returns 422 for a single non-black band (4 ms)

✓ returns 6K8 for blue, grey, red (2 ms)

PASS ./service.test.js

resistance

one band

✓ returns 0R for a single black band (1 ms)

✓ throws an error for a single non-black band (5 ms)

two bands

✓ throws an error (1 ms)

three bands

✓ returns 20K for red, black, orange

✓ returns 21K for red, brown, orange

✓ returns 22K for red, red, orange

✓ returns 23K for red, orange, orange

✓ returns 24K for red, yellow, orange (1 ms)

✓ returns 25K for red, green, orange

✓ returns 26K for red, blue, orange

✓ returns 27K for red, violet, orange

✓ returns 28K for red, grey, orange (1 ms)

✓ returns 29K for red, white, orange

✓ throws an error for a leading black band

✓ returns 12K for brown, red, orange

✓ returns 32K for orange, red, orange

✓ returns 42K for yellow, red, orange (1 ms)

✓ returns 52K for green, red, orange

✓ returns 62K for blue, red, orange

✓ returns 72K for violet, red, orange

✓ returns 82K for grey, red, orange

✓ returns 92K for white, red, orange

✓ returns 22R for red, red, black

✓ returns 220R for red, red, brown

✓ returns 2K2 for red, red, red

✓ returns 220K for red, red, yellow (1 ms)

✓ returns 2M2 for red, red, green

✓ returns 22M for red, red, blue

✓ returns 220M for red, red, violet

Test Suites: 2 passed, 2 total

Tests: 33 passed, 33 total

Snapshots: 0 total

Time: 0.363 s, estimated 1 s

Ran all test suites.

Note: most of the service-level tests take less than 1ms (so the time isn't reported), whereas all of the API-level tests take more. This is another reason it's useful to keep business logic independent of the transport layer (and others, e.g. a persistence layer for talking to a database) - testing the basic logical code is generally much faster than dealing with the frameworks and connections that come with those other layers.

Once everything's passing, make a commit.

Four bands [7/9]

We can handle all valid one- and three-band resistors at this point, plus some invalid one- and two-band cases. So let's handle resistors with three value bands, adding an extra significant figure to the value.

Again it's important to think about the cases we're going to choose to ensure our code works correctly. I would suggest at least three, based on the structure of the output:

- Where the multiplier is a multiple of 3 (0, 3, 6, 9), i.e. the band is black, orange, blue or white, we already showed three digits, e.g.

"120R"; - Otherwise, we only showed two digits before, e.g.

"12K"or"1M2", so we're adding a third digit; - Unless the third value band is black, in which case we still shouldn't show a trailing zero.

Here the cases we've selected have a meaning, so the name should clarify that meaning to the reader rather than just e.g. "returns 123K for brown, red, orange, orange":

describe("four bands", () => {

it("adds a third digit in the middle", () => {

expect(resistance(["brown", "red", "orange", "orange"])).toBe("123K");

});

it("adds a third digit at the end", () => {

expect(resistance(["brown", "yellow", "violet", "brown"])).toBe("1K47");

});

it("does not add a trailing zero", () => {

expect(resistance(["blue", "grey", "black", "green"])).toBe("68M");

});

});

Introduce these tests (along with an API integration case, if you like), get everything passing and make a commit.

Paradox of tolerance [8/9]

Now we're going to add a fourth rule of resistors:

- A resistor may have a tolerance band (otherwise its tolerance is ±20%), unless it's a 0Ω resistor.

We'll cover five possible cases here, which include two new band colours and reuse two of the existing colours:

| ±20% | ±10% | ±5% | ±2% | ±1% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No band | gold | silver | red | brown |

This is, as you may just have realised, a bit of a problem. If the tolerance band is optional, then what is e.g. brown, green, yellow , red describing:

- 15,400Ω ±20%; or

- 150,000Ω ±2%?

Obviously that's quite a big difference; the circuit probably isn't going to work correctly if you use the wrong one! On the physical packaging this is indicated by a gap - the value and multiplier bands are at one end of the resisistor, the tolerance band is at the other. Perhaps we could do something similar, adding a separate parameter at the service level and a separate query parameter to the HTTP API? For example, maybe something like:

$ curl 'http://localhost:3000/resistance?bands=brown&bands=green&bands=yellow&bands=red'

15K4 ±20%

$ curl 'http://localhost:3000/resistance?bands=brown&bands=green&bands=yellow&tolerance=red'

150K ±2%

Here we're changing the responses for existing requests - now rather than "150K", we get "150K ±20%". I'd suggest making this change first, as a separate commit, then moving on to include the actual tolerance bands. It's still "0R" for a single black band, a 0Ω resistor never has a tolerance band.

Design the API and test-drive the implementation of your choice, starting with an integration test then driving out the full functionality through some unit tests.

Once you're happy, make a final commit - we're done!

Exercises [9/9]

Here are some follow-up tasks for further practice (remember to test-drive anything you work on):

- Predict and then check happens if you make a request where the bands aren't recognised colours (e.g.

GET /resistance?bands=fuchsia&bands=goldenrod&bands=octarine) and/or there are multiple tolerance bands. Did you predict correctly? Do you think it's the right behaviour - do you consider that request to be semantically or structurally invalid, and does the current implementation reflect that? If you think it should behave differently, update accordingly. - Return to step 4 and try out some different orders for introducing the three-band cases - did I suggest the right route, how much difference does it make?

- Design and develop a different HTTP API (i.e. changing any or all of the request method, request path, use of query parameters or structure of the response body).

- As well as the value, multiplier and tolerance bands, resistors may have a temperature coefficient band - implement support for this.

- There's a set of preferred numbers that resistors are generally designed to (e.g. for the default ±20% tolerance you'd get resistors only in multiples of 1.0, 1.5, 2.2, 3.3, 4.7 or 6.8) - introduce a "strict" mode in which non-preferred resistors are invalid inputs.

- Write a CLI to expose the core functionality on the command line (access any arguments via

process.argv; you can use Node's built-inparseArgs, available from v16.17/v18.3, to help you out if you want to allow some non-positional arguments e.g.node cli.js red green blue --strict). - Write a React app that consumes the HTTP API to allow a user to interactively determine the shorthand for a given set of bands - as you do so you may realise you need to change the API to support the UI, feel free to do so and read up on consumer-driven API development.

- Try writing the tests with a different HTTP client (e.g. Axios, fetch) instead of Supertest.

I'd recommend creating a new git branch for each one you try (e.g. use git checkout -b <name>) and making commits as appropriate.

Comments !